Tinged with a touch of insomnia, I woke at 2:35 a.m. Wednesday and wondered whether I would fall back to sleep. When an answer didn’t arrive 10 minutes later, I was up and at ‘em.

Perseus is a circumpolar constellation for anyone living north of 40 degrees latitude. I’m at 44 degrees north latitude. Each day up to 85% of the constellation slips below the horizon. The constellation was first charted and presumably named by Ptolemy in the 2nd century. Perseus is forever chased by the magnificent star Capella (magnitude -0.48), which hides below my horizon for about two hours every day.

Early Morning Coffee with Perseus

Perseus is known primarily for three things: The August meteor shower, the California nebula and the famous double cluster. I discovered a fourth claim to fame two mornings ago.

Here’s that story:

A half hour later after stepping out under the early-morning stars, I had a steaming cup of coffee on the ground next to me, the SeeStar was aligned and leveled and turned toward NGC 896, also astronomically catalogued as IC1805 and Sh2-190 and colloquially known as the Heart nebula or the Running Dog nebula; the latter nickname is now a personal preference. The Running Dog nebula may have flashed through my field of view in years past when my younger self swept over Perseus with two Edmund Scientific Company reflectors—the three-inch purchased in 1967 and the eight-inch purchased in 1985—or the little Celestron C90 bought a 15 years ago and sold three years later, or the 11×80 spotting scope I gave to me daughter, or the Vixen eight-inch modified Maksutove-Cassegrain that I’ve had for a couple of years.

I never saw the Running Dog with past and present gear, but thanks to the SeeStar S50—which told me it might be something I want to see—the Running Dog ran right to my field of view on July 18, 2024.

The Running Dog was first recorded by William Herschel on Nov. 3, 1787. Like everything else in the cosmos, there’s an abundance of hydrogen in the nebula, back lit and ionized by a small group of young hot stars fifty times larger than the sun. Add sulphur and oxygen into the soup, step back 6,150 light years and behold, a dog chases across the night sky. In my photo, exposed for four minutes, the dog appears to be running towards the upper lefthand corner. Let’s do some doggy baby talk. Say it with me: You’re such a good boooooy.

The Double Cluster

Two more better-known clusters in Perseus caught the lens of the SeeStar in the pre-dawn Wednesday sky: Caldwell 14, which is composed of two NGC clusters numbered 869 and 884. But let’s face it, if you tell an astronomy mate that you looked at the double cluster in Perseus, they immediately know what you’re talking about. Hipparchus, known mainly for inventing trigonometry, first catalogued the two funky groups of stars in 130 BC.

Herschel, who gets credit for most everything, identified the double cluster as a double cluster in the 19th century. But way before Herschel, Johann Bayer may have identified them as such in his New York Times bestseller, Uranometria, published in 1603. My first-edition copy is a little dog-eared and it looks like tomato soup stained page 14.

The most interesting thing about the Perseus double cluster is that each cluster is relatively close to one another. One is 7,640 light years from us and the other is 7,460 light years away. Both are barreling toward us at 24 miles-per-second. In the half-hour it took me to write this post, they’ll be 43,200 miles closer to us. Don’t bother looking to see if they’re bigger from one night to the next. They are, but they aren’t.

The double cluster is also home to hundreds of super hot giant stars. These are the engines that illuminate both groups. Had these supergiants been off by themselves in our part of the galaxy—solo birds sailing among the stars—we likely wouldn’t be able to see them. But together, those supergiants radiate the energy thousands of times more stronger than our sun.

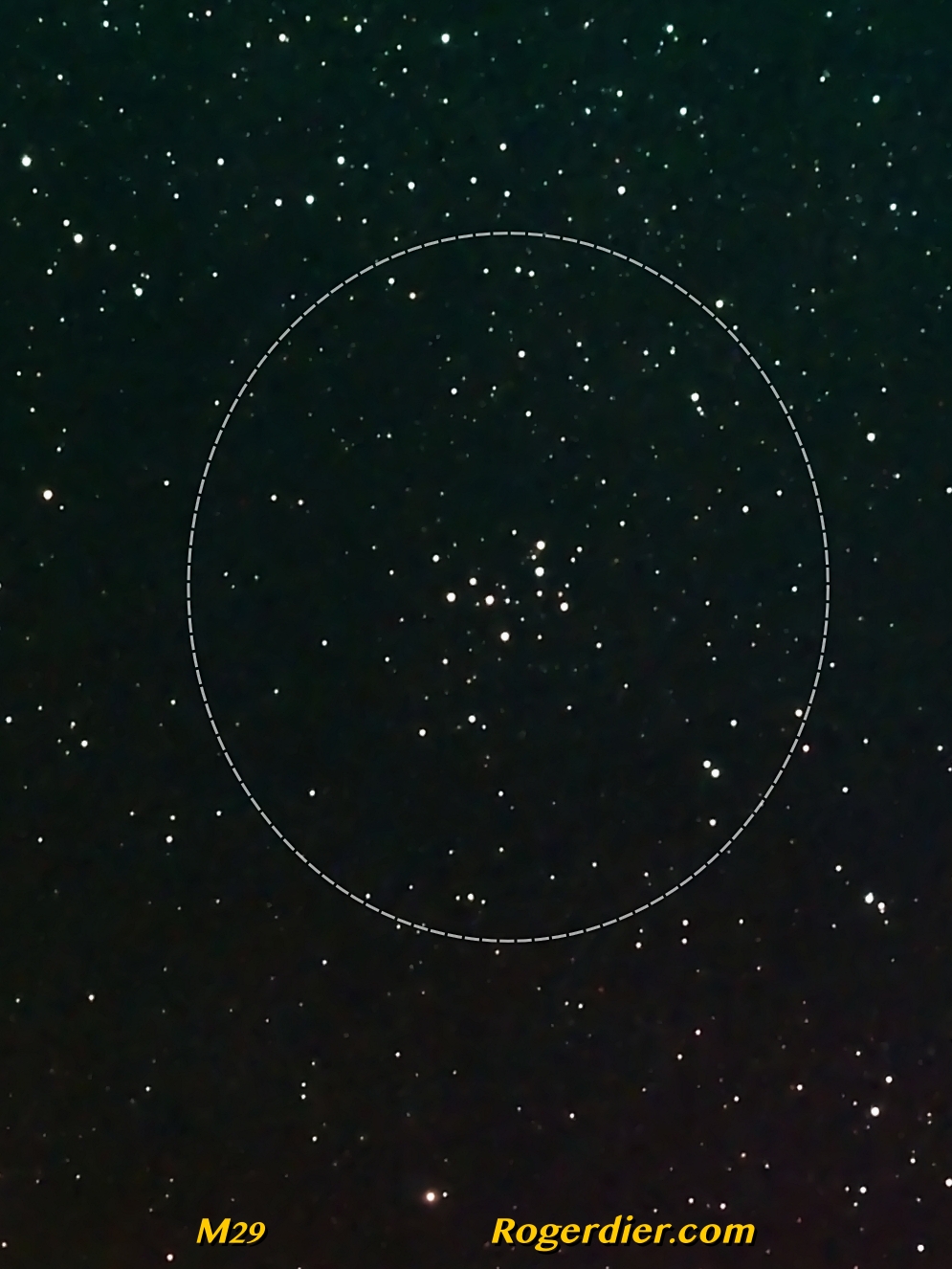

M29

Another open cluster I photographed Wednesday morning is M29. It is much smaller than each of the two Perseus clusters, but it is within two degrees of the supergiant star Sadr, which is the sixth brightest star we can see and is the center star of the Cygnus summer cross. With a combined magnitude of 7.1, M29 should be visible in binoculars. The brightest stars of M29 form a quadrilateral and another three stars north of the quadrilateral form a triangle. It look like a squished dipper.

On behalf of the burgeoning staff at Rogerdier.com, thank you for reading. Here’s to the good health of you and yours, and may all your night skies be free of clouds and artificial illumination.

Proudly Powered by WordPress

3 responses to “The Heart Nebula Dogs It”

Interesting nebula. I’m not sure I see a “heart” or even a “dog” but that’s just me.

LikeLike

It’s always good to hear from you Roger. The equipment that I’m currently using is not high-end, but for the price, I have been pleased with the photos it delivers. Like most things celestial, it helps to have an imagination to see what the ancients or first nation people saw in the night sky. I can see the dog’s rear legs and body, but you have to fill in the rest to see his head, etc. Many people enjoy your site and your photos. I am one of them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Roger. The Seestar and it’s competing brands Vespera and Dwarf are becoming popular, especially with newcomers to astronomy but also with some older enthusiasts who downsize due to have difficulties lifting their heavy gear.

I’m not in the market for one but I am in the process of regenerating my Star Adventurer DSLR set up, partly to save me from having to dismantle my refractor when going on a field trip with other Society members.

LikeLike