Our normally sedate neighborhood was lit up and lively on Wednesday night, July 24th. I had planned to send the SeeStar S50 to look for Comet 13/Pons-Olbers, but a neighbor’s tree blocked that part of the western horizon. I took a long exposure of the North American nebula, hoping to catch what some call the Red Band, a hydrogen cloud that is the backbone of the North America Nebula. The red band is not to be confused with the yellow band near the top of the north col of Mount Everest. The 14-minute exposure showed part of what I wanted to see.

The next evening, I drove to Ames Point, a manmade peninsula that juts out a quarter-mile or more into Lake Winnebago. The paved 15-feet-wide path is populated by walkers, joggers and bicyclists during the day. On chilly days of spring and fall, ducks and geese have been noon to snooze in the sun while sitting on it. The Ames Point peninsula gives amateur astronomers an unvarnished view of the eastern horizon, and a pretty good view of the western horizon.

There were four cars of people somewhere on the path when I arrived in the shadowy gloaming. The wind off the lake was surprisingly sustained and strong from the east, so the tripod landed on an incline on the western side of the path, shielded a little from the wind.

WE LIVE. WE LEARN.

It takes about five minutes to orient the telescope to the magnetic north and get it level. Once done, I asked it to find the comet, which was about 25 degrees above the northwest horizon in the tiny constellation Leo Minor. Moments later, a hazy spot appeared on my screen. Concerned about the sustained wind blowing off the lake, I left the pavement and positioned myself two-feet from the SeeStar’s tripod to shield the rig from the shaking wind. I pushed the magic button and the stacking began, haltingly. It took forever for the 10-second stacks to be accepted and added to the existing pile.

Standing there, watching my phone, I couldn’t figure out why it wasn’t on track to stack. Was it the wind? Did it need to be re-leveled? The picture parade stopped. Nope; the SeeStar was still level, still fully charged. I started over again, shifting my weight gently from hip to hip. The second shoot began. The stacking limped along, and then permanently quit around 50 seconds. Nevertheless, The SeeStar kept trying. Agitated, I continued to shift my weight from one side of my body to the other. The minutes ticked on, pushing Comet Olbers lower toward the horizon. I started over a third time. The frustrating repetition continued.

I stopped the tracking and left the slight incline of the hill and walked down the path to think. What do I know about the SeeStar’s tracking? When the scope is happy, it’s level, the object it’s photographing is well above the horizon, it knows where magnetic north is and keeps the object glued to the perfect middle of the field of view.

Let’s try one more thing. I walked back to scope and from the pavement, asked it to try again. Bingo! The images stacked up quickly, like poker chips of a winning player. What happened ? Your intrepid astronomer banged his head with the heel of his hand. The problem was me. The good intentions to shield the scope from the wind created the problem. Transferring my weight from foot-to-foot and side-to-side pressed down the surrounding sod, imperceptibly shifting it, including the ground on which the tripod stood.

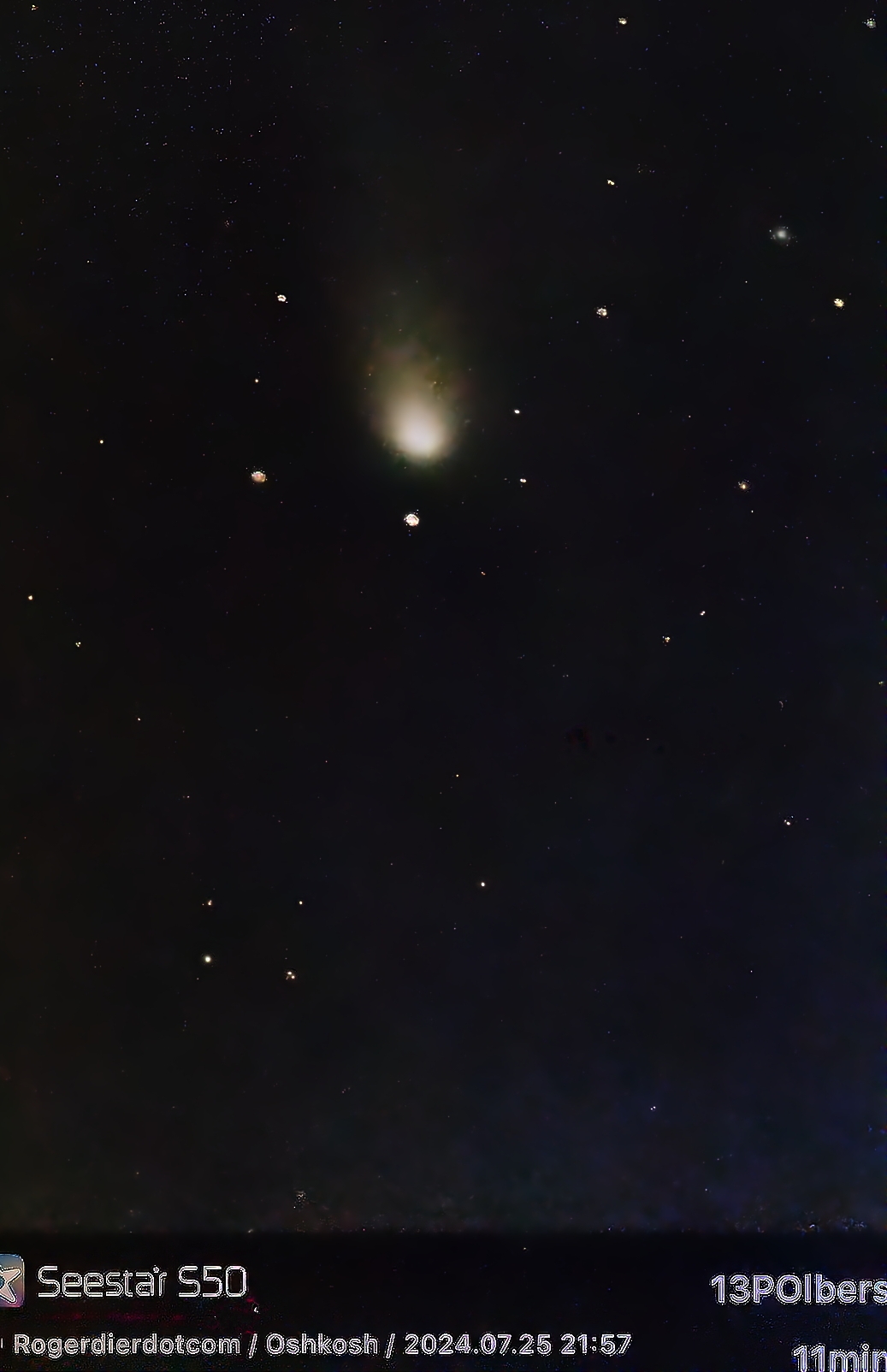

COMET 13P/OLBERS

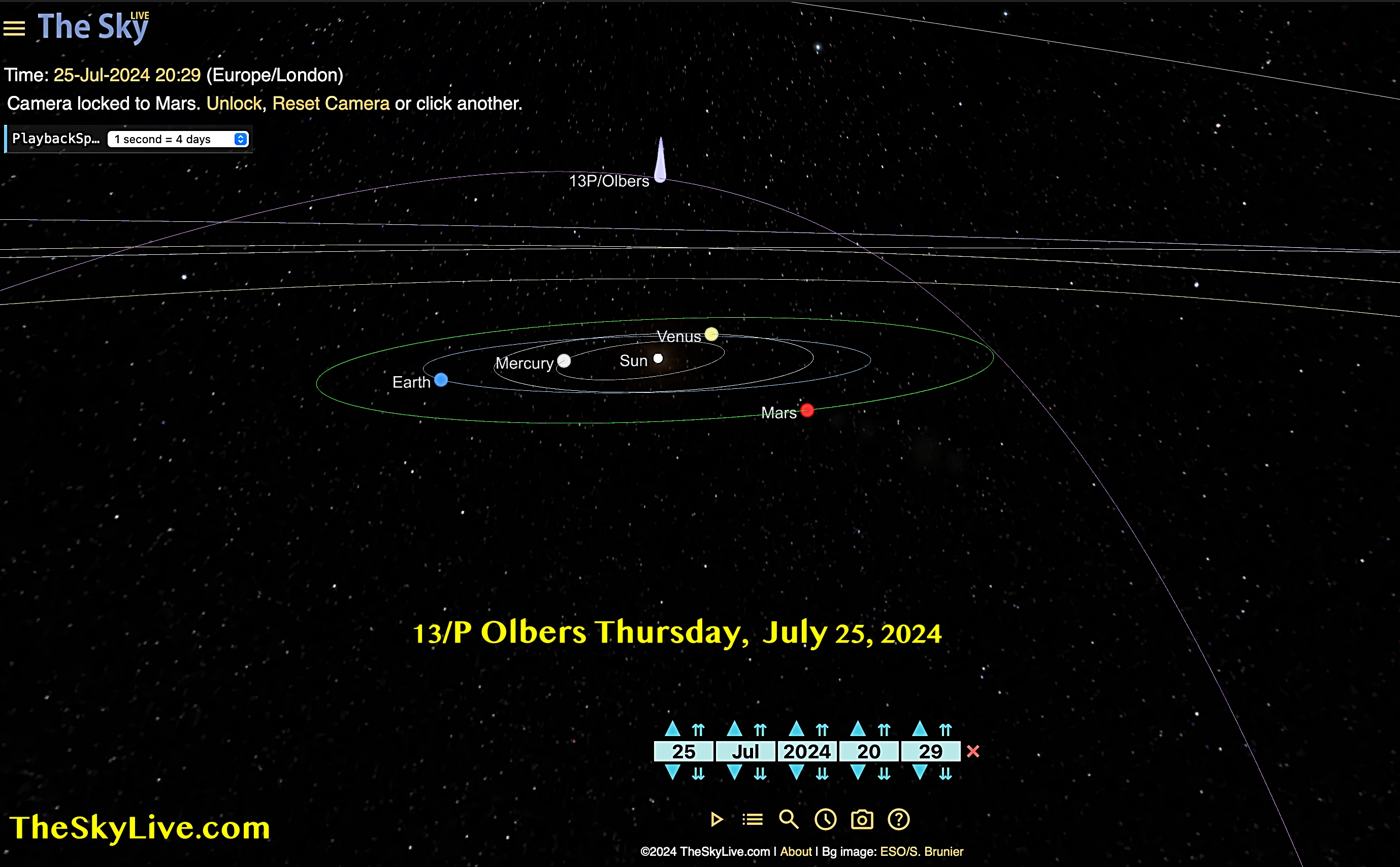

Traveling counterclockwise around the sun, Comet Olbers reached perihelion on June 30, or 25 days before it appeared in the field of my SeeStar S50. The last time Comet Olbers swung by that close to the sun was on June 19, 1956, or about a year after I was born. With an orbital period of 69.3 years, it won’t be as close to the sun again until March 20, 2094. There’s an excellent chance Olbers will be here again in 2094. There’s zero chance I will be.

Olbers is around magnitude 7.6 this week, and it’s moved out of the boundary of Leo Minor into Ursa Major. The tail under pristine skies is as wide as the moon or sun, or 30 arc minutes. If you want to see the comet or photograph it, know that the moment is now. In a year’s time, Olbers will be 17th magnitude. Good luck with that.

My photo of Olbers took 11 minutes to make, meaning these are 66 frames stacked on one another. The wind obviously affected the focus of the photo, as did the forest fire haze from points north and west. Thanks to haze and wind, it’s not the best, but that night, it was the best I could do.

WIKIPEDIA HISTORY OF OLBERS:

Heinrich Wilhelm Matthias Olbers was born in Arbergen, Germany, today part of Bremen, and studied to be a physician at Göttingen (1777–80). While he was at Göttingen, he studied mathematics with Abraham Gotthelf Kästner. In 1779, while attending to a sick fellow student, he devised a method of calculating cometary orbits which made an epoch in the treatment of the subject,[1] as it was the first satisfactory method of calculating cometary orbits. After his graduation in 1780, he began practicing medicine in Bremen. At night he dedicated his time to astronomical observation, making the upper story of his home into an observatory.

In 1800, Olbers was one of 24 astronomers invited to participate in the group known as the “celestial police“, dedicated to finding new planets in the solar system. On 28 March 1802, Olbers discovered and named the asteroidPallas. Five years later, on 29 March 1807, he discovered the asteroid Vesta, which he allowed Carl Friedrich Gauss to name. As the word “asteroid” was not yet coined, the literature of the time referred to these minor planets as planets in their own right. He proposed that the asteroid belt, where these objects lay, was the remnants of a planet that had been destroyed. The current view of most scientists is that tidal effects from the planet Jupiter disrupted the planet-formation process in the asteroid belt. On 6 March 1815, Olbers discovered a periodic comet, now named after him (formally designated 13P/Olbers).

NEXT TIME

On the next Rogerdier.com post, we’ll share pictures of globular clusters taken this past week and introduce a nebula that is new to us, the Pacman.

Art and information credits go to USA Today, Accuweather, TheSkyLive.com, Wikipedia and Nat King Cole.

4 responses to “Those Hazy Crazy Lazy Nights of Summer”

Nicely captured, despite all the difficulties you experienced.

Does the Seestar follow the motion of the comet when it stacks each frame or is it limited to sidereal tracking?

LikeLike

Hello Friend. I don’t know and I’m trying to find the answer. It does offer a menu of objects worth seeing every day, and comets are sometimes included. So if they are, and the introduction of A means that B can follow A, then I’d say yes. But I’ll find out for sure. By the way, every time this comet comes to mind, I think of your birth-to-know relationship with it. Thank you again for sharing that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Should be “birth to now relationship.

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLike