I originally planned to do a segment on globular clusters that I photographed last week, but like clouds rolling in during a nighttime observing session, plans changed.

BECOMING DUCKY

The Wild Duck Cluster is really wild. It’s topic A.

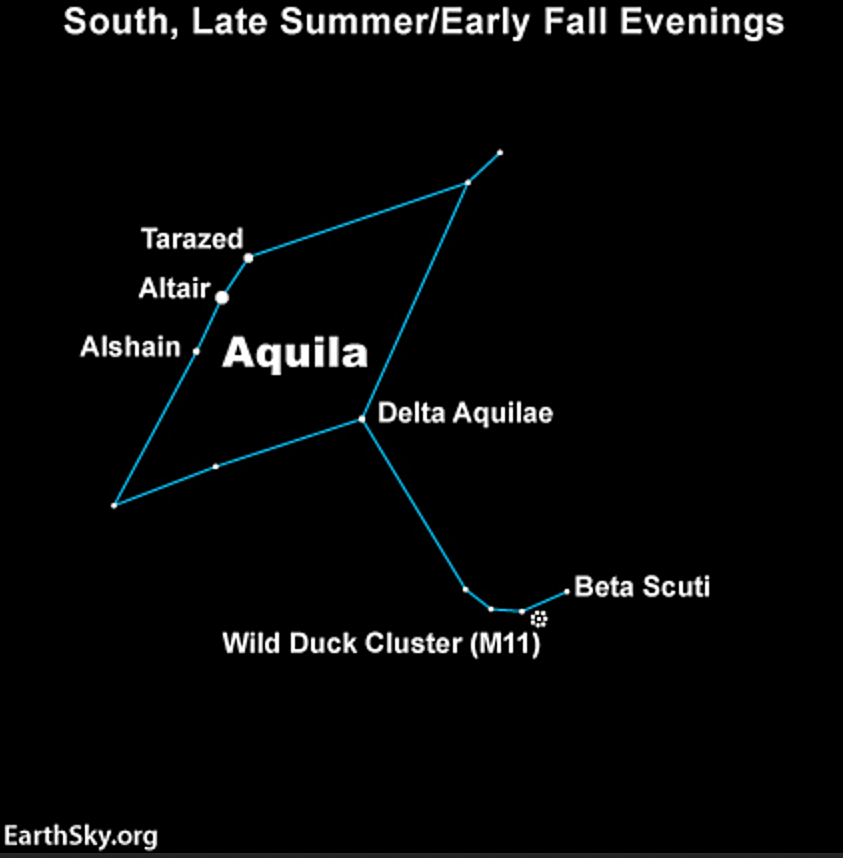

Also known as M11, the Wild Duck Cluster has an apparent magnitude of between 5.8 to 6.3. Under the dark-as-death skies of the ancients, sharp-eyed people undoubtedly noticed the smudge as an extremely faint, odd-looking star, or stars. If they had written language and wrote down what they think they saw, nobody can find it now.

In 1681, a German, Gottfried Kirch, first recorded M11’s existence through one of the many telescopes he built. Fifty-two years later, Englishman William Derham identified the cluster as a resolvable group of stars. Two-years later in 1735, another Englishman, Royal Navy officer Admiral William Henry Smyth, peering at the cluster through a telescope, noted the V-shaped pattern of stars. It reminded the Admiral of “a flight of wild ducks.”

No one could resist that nickname. In 1764, Charles Messier cited the Wild Duck Cluster as the 11th item in his catalog of things that look like comets but really are not. There we have it: Over the course of 83 years, a German, two Englishman and a Frenchman brought us to now. Who says nations can’t work together?

A LOOSE GLOBULAR OR TIGHT OPEN?

To look at it, we could ask if the stars were the most compact of open clusters or the most loose of globular clusters? Given the dominant elements of its members, their age, and most importantly, the location of the cluster, settled wisdom knows it as an open cluster. In the evolution of language, open clusters were commonly labeled as galactic clusters in my youth. Open works better.

The brightest and most populous stars in the group are blue giants, full of heavy metals. But there are some big red and yellow furnaces in there, too. The cluster formed between 220 and 250 million years ago. From our point-of-view, M11’s stars are a long way off in one of the spiral arms of our galaxy, some 6,120 light years away. And, from where you are looking at it, M11 is big—14 arc minutes in diameter—almost a third of the diameter of the full moon. Though not figuring in the design of the constellation Scutum the Shield, the cluster is situated within its boundaries.

HD174208 AND FRIEND

See that bright orange star in the top right corner of my SeeStar S50 photo? That’s HD174208. It’s an orange-red supergiant, which is 72 times bigger than the sun and 1,620 times more luminous. This orange supergiant is 1,744 light years from us and it shines near the limit of visual magnitude, 5.9.

At about 5:30 on the clock below HD174208 is HD174209, which is another orangish double star. It’s a lot closer to us at 245 light years away and only slightly bigger (2.3 times larger than Sol) and slightly more luminous (3.78 brighter than the sun). Though considerably closer than HD174208, it’s dimmer: We see it as an 8.09 magnitude star.

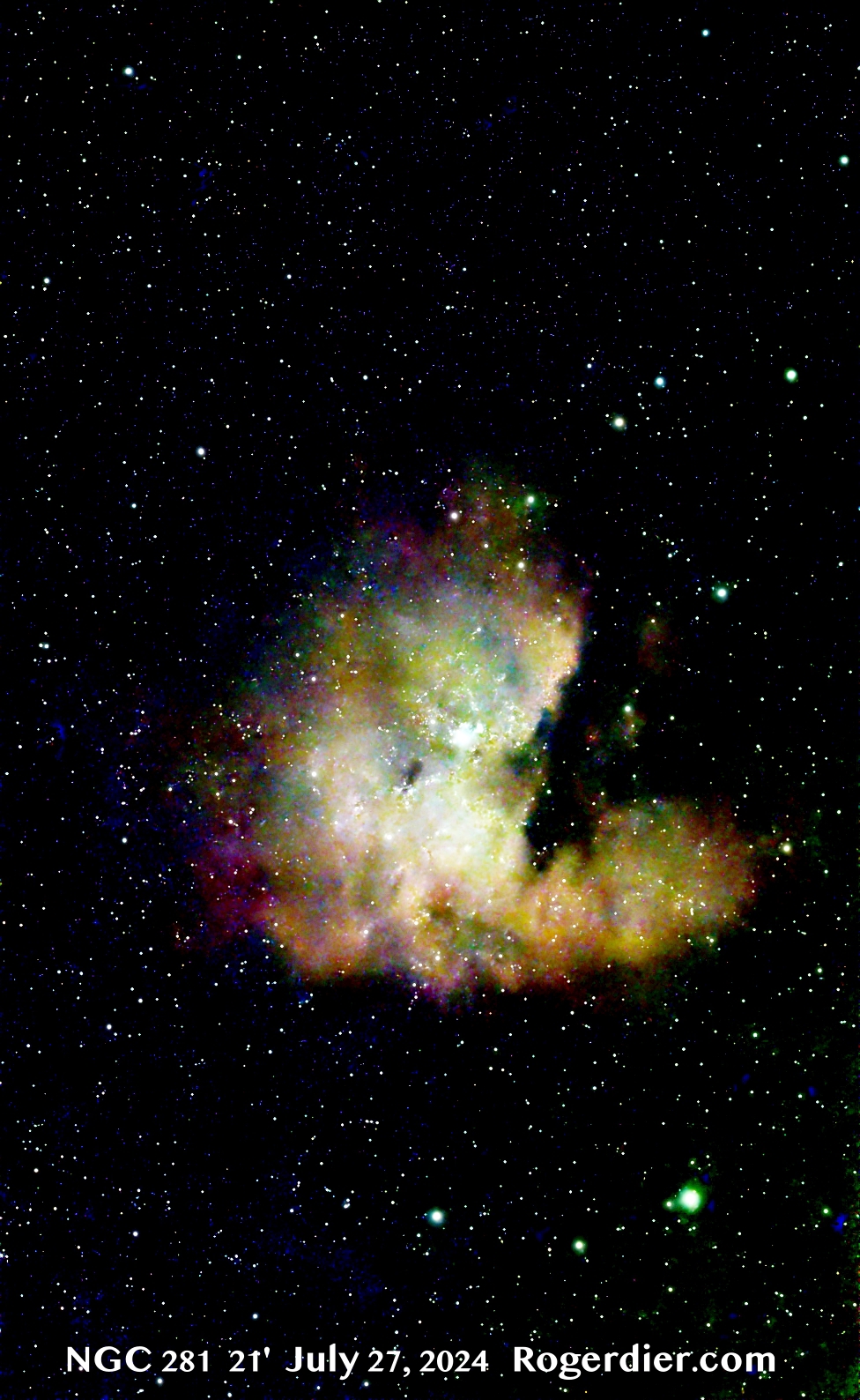

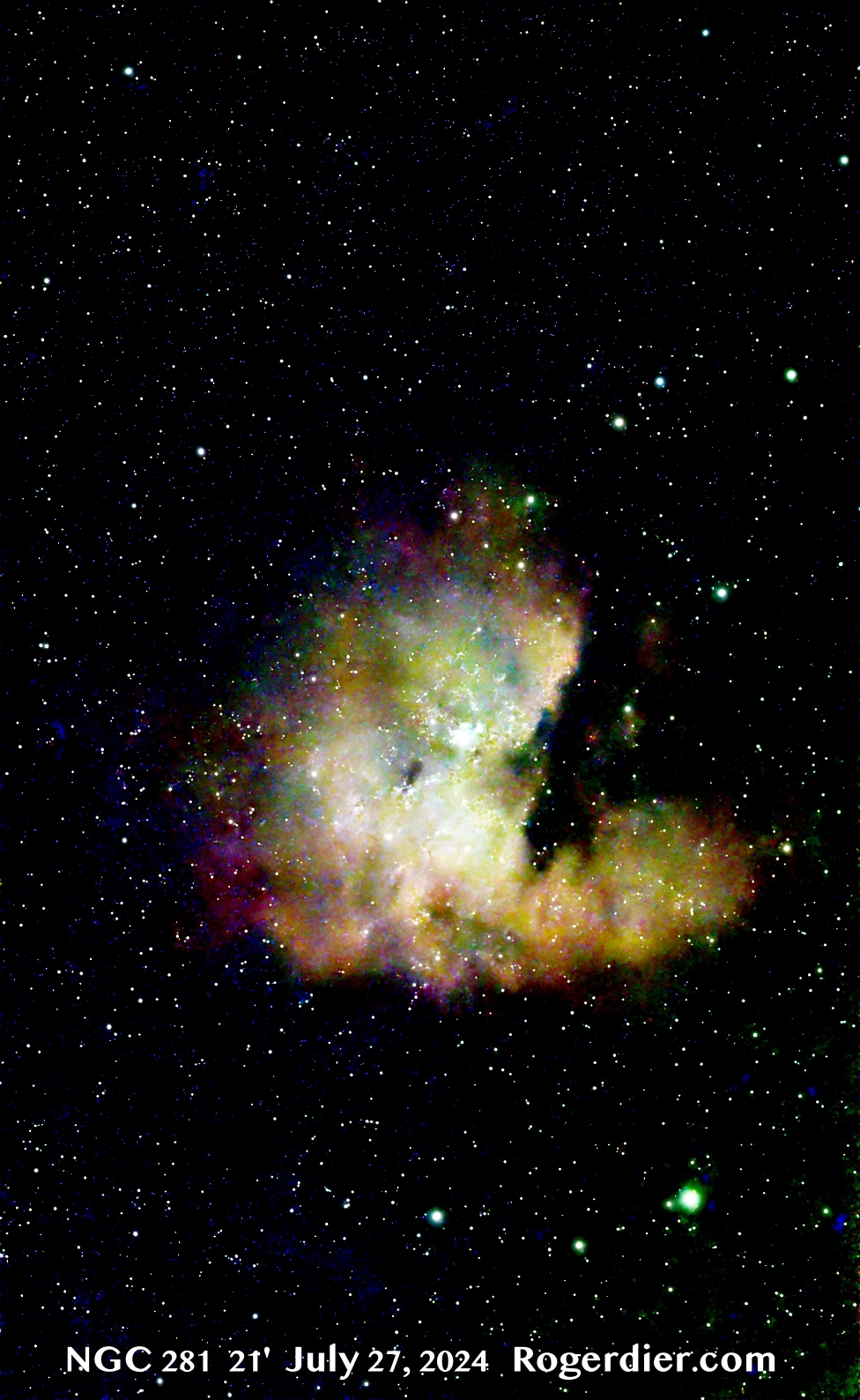

THE PACMAN NEBULA

This nebula is the cover photo of this post. When I found it on the kinda-clear night of July 27th, I decided to shoot it to see how much of a Pacman the Pacman really was. It took about four minutes of exposures by my modest 2-inch lens to generate a faint outline of what you see before you. Intrigued, I decided to see where this would go if the SeeStar S50 stayed on it, and it tracked well for 21 minutes, one of my longest exposures.

Though the emission nebula has a charming colloquial name, professional astronomers know it as NGC281. The light of the nebula is generated mainly by a group of five stars. A writer on the SkySafariPlus App describes it as “a busy workshop of star formation.” I like that. Remarkable to your intrepid astronomer is the dark nebula in the center of the cloud that floats in silhouette in front of the nebula. That dark cloud must be several light years in height, width and thickness.

The Pacman Nebula existed for eons unrecorded until E.E. Barnard looked at it in August 1883. Barnard described it as “a large faint nebula, very diffused.” The nebula’s namesake would not be invented for 97 years after Barnard first catalogued it. I’m quite sure Barnard did not dub it the “Pacman Nebula.”

Walter Scott Houston, a hero to many amateur astronomers of the American Baby Boomer generation, wrote of NGC281 in his book Deep Sky Wonders: “There was a faint glow in the immediate vicinity of the multiple star, with an occasional impression of a much larger star.” Houston, who also wrote for Sky & Telescope magazine back in the printed-issues era, said the surface brightness of the nebula was akin to M33 and NGC205, the latter a companion of the Andromeda galaxy. Houston, who left us in 1993 after 81 years on the planet, was born in Tippecanoe, Wisconsin, right next door to the town of Tylertoo.

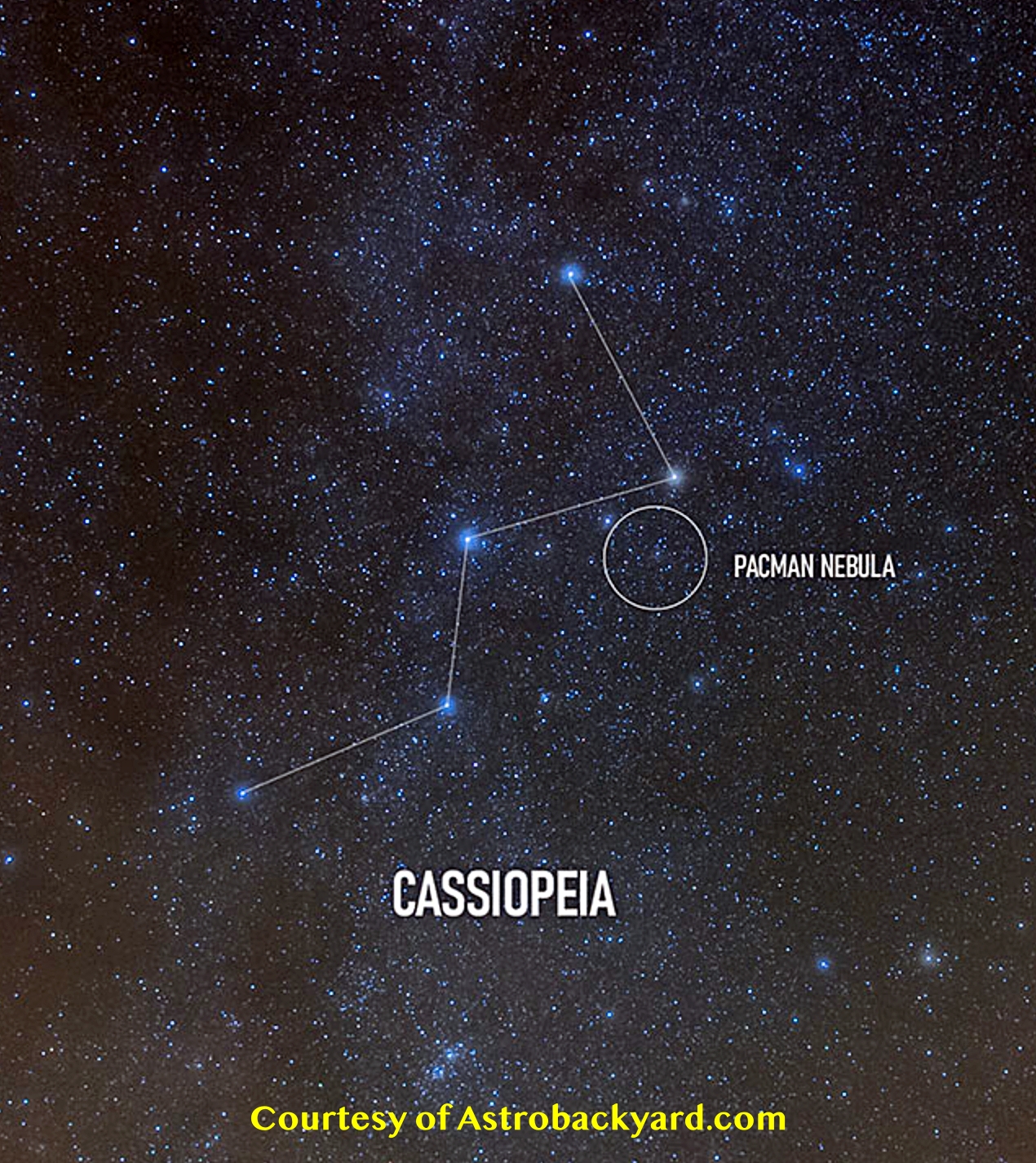

CASSIOPEIA LAYS CLAIM

The Pacman is in the Perseus arm of our galaxy and is 9,500 light years from us and 25 million light years wide. Fewer than a million years old, the magnitude 7.4 light we see tonight left the Pacman shortly after the Ice Age ended. With an apparent diameter of 35 by 30 arc minutes—or 41.5 light years wide, a real fatty—an observer needs a dark sky, a small scope or good binoculars to spot it.

Because the Pacman Nebula is in Cassiopeia, it’s circumpolar to Northern hemisphere observers and is visible year round. The higher the W of Cassiopeia is in your sky, the better it will look. Though we who live north of the equator can see the Wild Duck Nebula, it doesn’t climb high in our sky, nor is it visible year round. People in the southern hemisphere see the Wild Duck higher in their sky and it’s visible more often.

Bottom line: There’s plenty of objects to see in all skies above Earth.

Thank you for reading. Subscribe for free in the box found at the end of this post.

The staff of rogerdier.com wishes you good health and clear skies.