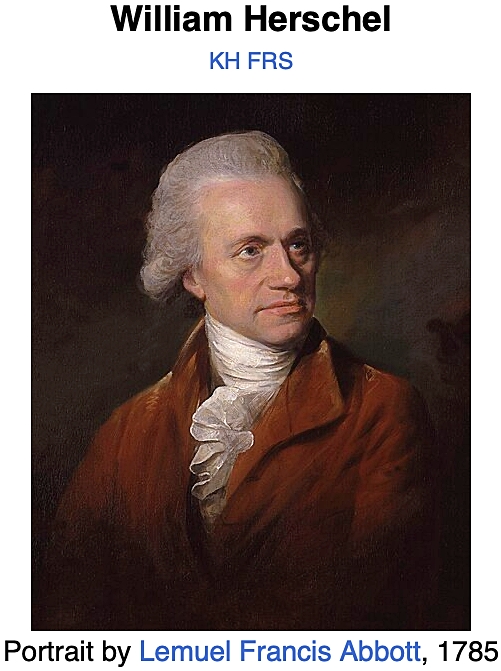

If you are reading this on Thursday, Sept. 5, 2024, William Herschel discovered the Veil Nebula 240 years ago today. Herschel, who sometimes spent 16 grueling hours a day grinding speculum metal he used as his primary reflecting element, lived at what he called Observatory House near Slough England, 20 miles west of London. His home was located at 52.88 degrees north latitude, and on that clear, late-summer evening near Slough, something caught Herschel’s eye as he swept across the great swan that is Cygnus. What Herschel glimpsed was the western filament racing away from the epicenter of a massive supernova. He was the first see the Veil Nebula, but others saw the star from which it came.

About 10,000 years ago, a brilliant star suddenly appeared high in the late summer sky. The star was so bright it was visible in daytime for months, perhaps a year or longer. Intact, this smashing star was 20 times the size of the sun, and when it blew, the farmers of Mesopotamia (northern Iraq), looked up from their barley and wheat fields and may have felt panic in the early days of its blazing appearance. The brightness that created the Veil Nebulas may have exceeded that of the full moon.

The events of the sky above are the earth below are unrelated, but as the brilliant new star blazed in the day sky, the glacial ice of the age was in recession. Also melting into extinction were short-faced bears, giant ground sloths, woolly rhinoceros, most woolly mammoths, cave bears, cave lions and saber-toothed cats. Big ones.

In time, the new star faded to black, undiscovered for centuries until Herschel, an interesting German-turned-British subject who discovered 2,400 cosmic sights during his lifetime. His best-known discovery is Uranus, using either his 6.2-inch, 12-inch or 18.7-inch Newtonian reflector. The talented Herschel likely discovered the Veil’s filamentary strands of heated, ionized gas and dust using his favored scope, the smallish one with the 6.2-inch primary. He liked it because it was portable. Many of us who own both large and small telescopes can relate.

Herschel described the western end of the nebula as “Extended; passes thro’ 52 Cygni… near 2 degree in length,” and described the eastern end as “Branching nebulosity … The following part divides into several streams uniting again towards the south.”

A year after discovering the Veil, Herschel began grinding a 48-inch plate of speculum metal that became the primary of his largest telescope, the one he called the “forty-foot” telescope because the tube was 40 feet long. Completed in 1789, it remained the largest telescope in the world for 50 years.

The Veil Above Oshkosh

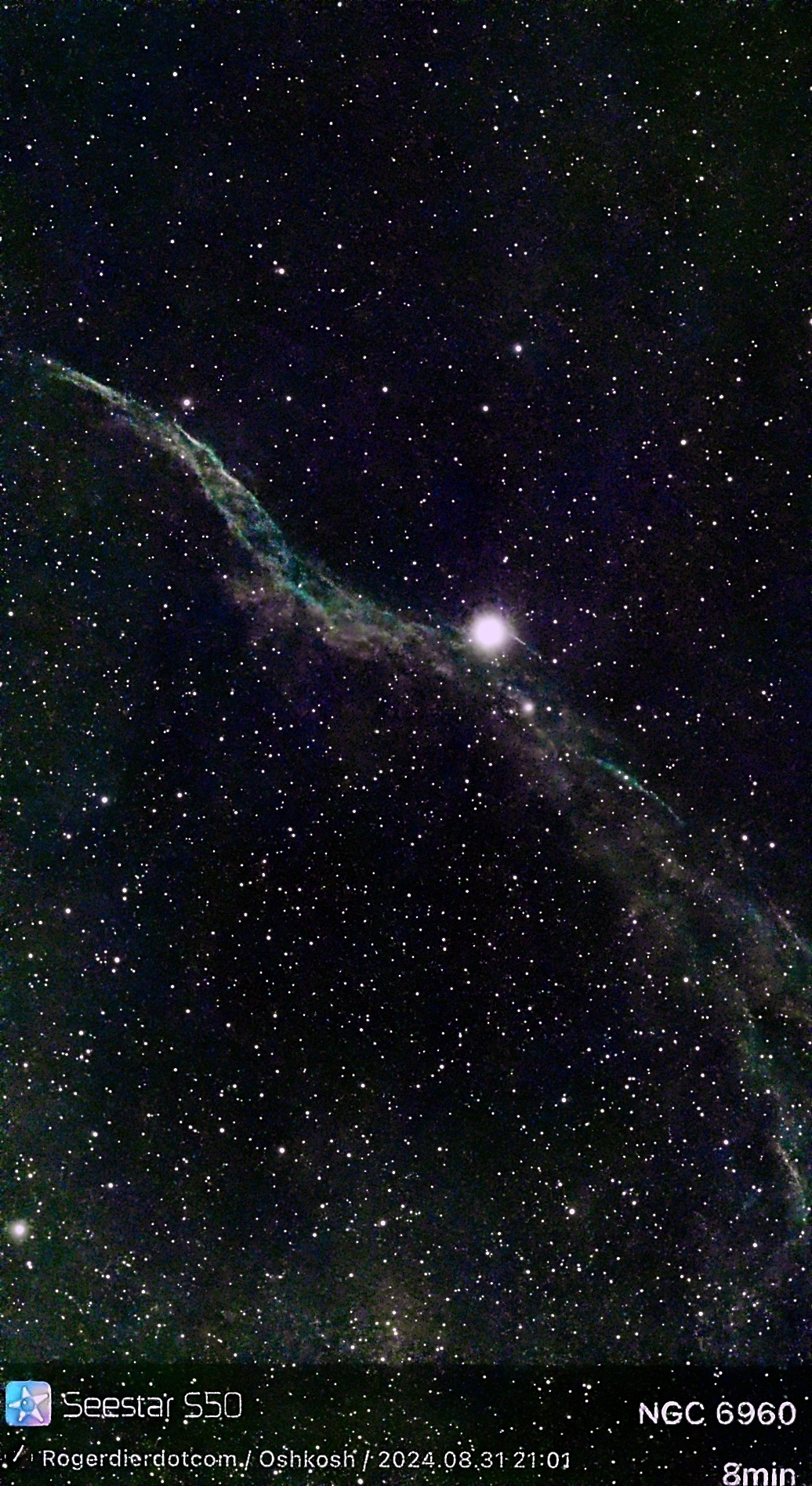

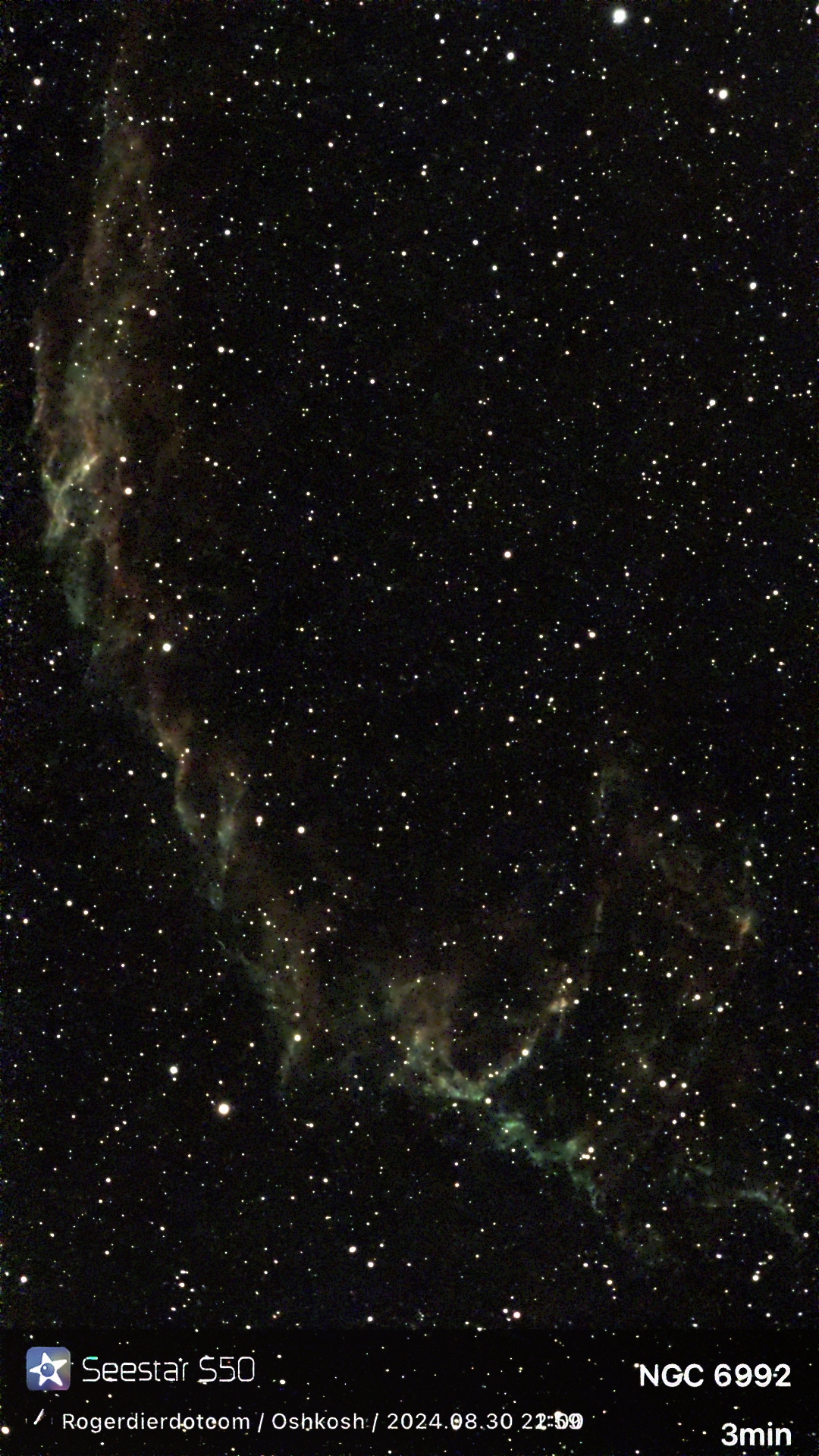

I turned the SeeStar S50 on the Veil a few times during the past 10 days. The Veil mainly consists of three sections, the eastern Veil, the western Veil, and the middle collection of fainter clouds known as Pickering’s Triangle.

I share one photo of the western veil, and two of the eastern filaments. The Western Veil features 52 Cygni, the one Herschel mentioned, a 4.22 magnitude diamond. The longer exposure of the eastern veil was poorly framed, and a three-minute exposure is added to give you a better sense of its shape.

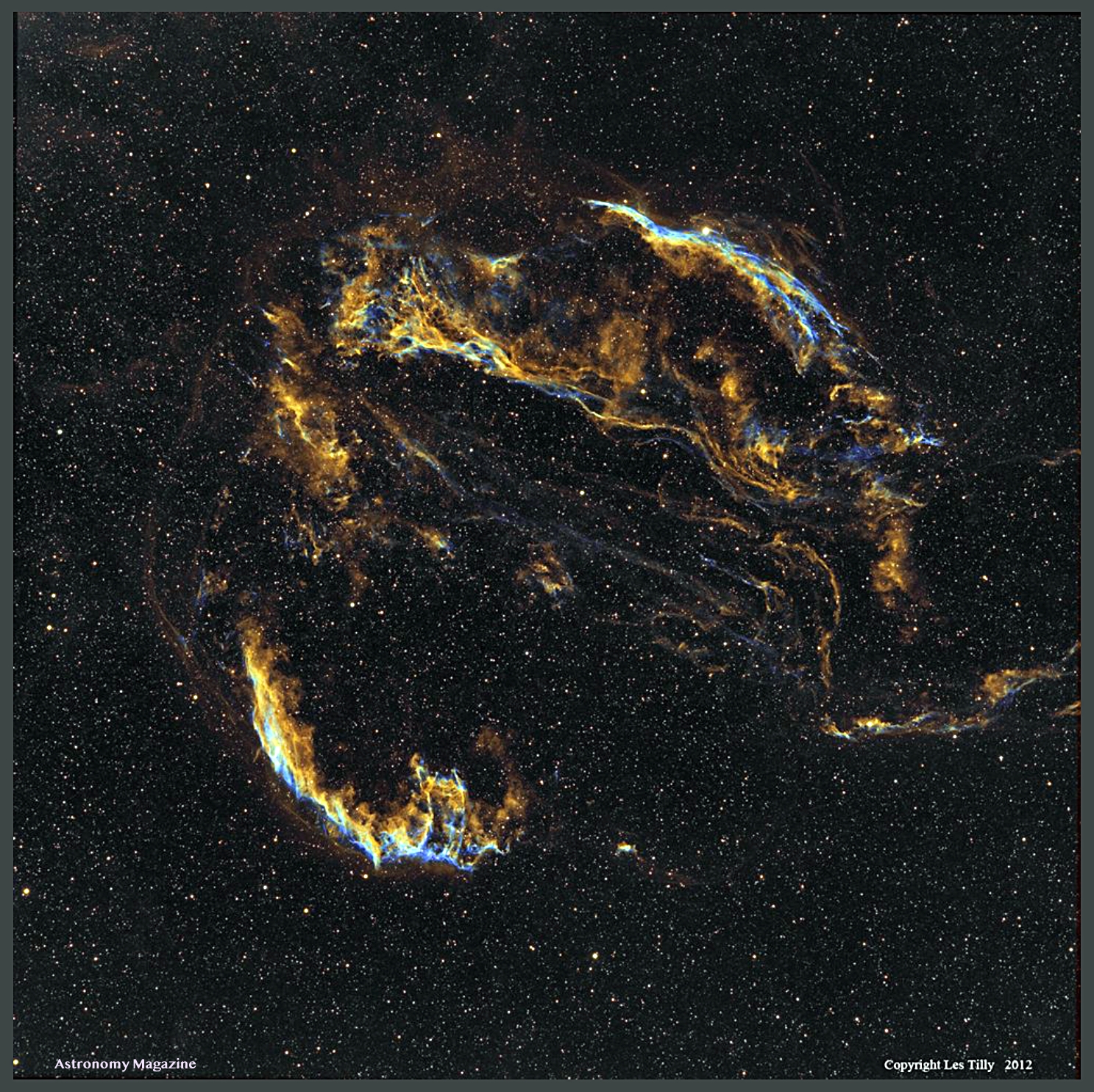

A dozen years ago, astrophotographer Les Tilly took a wide-angle shot of the Veil Nebula: east, west and middle Pickering. The Veil Nebula complex (NGC 6960/92/95) is 2,400 light years from Earth, and the energy of the explosion continues, with parts of the Veil receding from the long-gone Supernova at almost one million (938,000) miles-per-hour.

The Owl Cluster

One of the more entertaining things your intrepid astronomer discovered during this past week under the Bortle 6 Oshkosh light dome is NGC 457, popularly known as the Owl Cluster. This open grouping of stars lies in Queen Cassiopeia’s boundary, and features two brighter stars, which can be construed as owl’s eyes. The brighter one is Phi Cassiopeia, shining at magnitude 5 and the other is HD 7902, dimmer by two magnitudes.

Altogether, the open cluster is 7,900 light years from Earth, and of about 150 stars between 9th and 13th magnitude, 60 stars are actual members of this cluster. The other stars, including bright Phi Cassiopeia, are either foreground or background stars.

NGC 7822

Also known as the Question Mark Nebula, this 40-light-year-wide gas and dust cloud lies at the edge of a much larger molecular cloud in Cepheus. I’m fairly certain this is the first object I’ve ever photographed in that constellation. It was low on the horizon when photographed, and this shot is not one I’ll ever point to as a high-standard photo. In fact, I’m questioning why the Question Mark Nebula is even in this post.

Nevertheless, I’m glad the SeeStar snagged a representative number of photons, which traveled 2,900 light years to the SeeStar’s 2.1-megapixel Sony IMX462 CMOS sensor. Star babies are emerging from this emission nebula, meaning super hot electromagnetic energy from newer stars creates the whole light show. The main source of energy is BD+66 1673, which is an eclipsing binary system with a luminosity about 100,000 times that of the Sun. Wrap your mind around that kind of bright, if you can.

M31

Autumn approaches in the northern hemisphere and that means M31 rises in the Northeast. To see if a longer exposure could be done, I trained the SeeStar on M31 coming up over the trees. After SeeStar locked on like a bloodhound, I went into the house to visit with Michelina and work on some images taken earlier in the evening. About an hour later, I went outside and the SeeStar was still stacking 10-second exposures. I told it to stand down after a one-hour exposure. You see it here, along with flanking galaxies M110 (below M31) and M32.

Persian Power

In 964 CE, the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi first noted M31 as a “nebulous smear” and a “small cloud.” Charles Messier assigned it to his catalog in 1764. At 2.5 million light years away, M31 is the most distant thing humans can see without optical aid. My image, or any image, is not how it looks today. It’s how it looked 2.5 million years ago. At magnitude 3.4, it’s one of the brightest Messier objects and M31 is estimated to contain one trillion stars. The limited field of view of the SeeStar S50 cannot capture the wide girth of the galaxy. I wish it could.

There’s a new comet heading our way, and thanks to reader Kevin Mikkelsen, here’s a preview: https://youtu.be/qfCx2eqaNzM?si=HpNE6XQlEAG7DaDU

And a large thank you to a reader (gfamily) on cloudynights.com who offered a correction on Herschel’s main light gathering element of his telescopes. Herschel didn’t use glass, but speculum metal. Mirrors ground from glass were first used in the 19th century. Wikipedia states: (Speculum metal) was noted for its use in the metal mirrors of reflecting telescopes, and famous examples of its use were Newton’s telescope, the Leviathan of Parsonstown and William Herschel’s telescope used to discover the planet Uranus. A major difficulty with its use in telescopes is that the mirrors could not reflect as much light as modern mirrors and would tarnish rapidly.

That’s it for now. Thank you for reading. Please subscribe for free at the bottom of the page. It makes distribution of my posts so much easier and it’s my small ask of you.

Here’s to clear skies and to your good health and the good health of those you care about.