This week, on a fairly transparent night, I drove our vehicle about a half-mile out from the western shoreline of Lake Winnebago to go fishing. No, not for the prehistoric sturgeon that humans in nearby area zip codes like to hunker over and spear, savagely, through a rectangular hole in the ice, but to fish for familiar sights of the winter sky.

The night was finger-numbing. Our Rav 4 sat safely on about two feet of ice; that’s the fiction on which I staked everything. Other than arresting booms of shifting ice, it was quiet out on the ice. Heavy snow was late this year, arriving during the last half of February. I took the SeeStar S50 out of the back of the vehicle, walked about 40 feet south, turned it on, tuned it in to magnetic north, shoved the big tripod’s legs through a foot of snow until the legs found ice, leveled it and sent it to Orion’s bright variable Rigel for focusing purposes.

Telescopic Discovery

I took a seat in the vehicle and told SeeStar to find and photograph Messier No. 1, or M1 as it’s known in the community. Once upon a time in 1054, when it was first noticed in both the night and day skies by sky-watching cultures, it was a fantastic anomaly. The new star in Taurus the Bull may have been humankind’s first recorded Nova. Fortunately for us, living nearly a millennium later, written language had taken hold. So has storage of documents.

Early telescopic astronomers like Englishman John Bevis first laid eyes on what was left of the supernova in 1731. William Parsons, The Third Earl of Rosse, sketched it in 1844. Using his 36-inch speculum-mirror telescope at Birr Castle, County Offaly, Ireland, The Third Earl’s initial sketch of M1 looked like a crab. Later in his life, after The Third Earl built a telescope twice that size—also located at Birr Castle—the nebula looked nothing like a crab. But the original nickname stuck.

Once the French astronomer Charles Messier got a bead on it in 1758, he cited it as object No. 1 in his catalog of nebula that were not really comets.

The supernova that became the Crab Nebula was first spotted in mid-spring 1054. By July of that year, it first appeared in daytime at -4.5 and days later it was -7 magnitude, brighter than Venus and bright enough to show up during the day to compete with the sun.

The Pulse of M1

Since exploding 971 years ago, the remnants of that blast have spread out at 930 miles-per-second, or 0.5% of the speed of light. What’s left of the star that became M1 is now several light years wide, and it’s mostly hydrogen, the mother’s milk of the cosmos. What’s left of the pre-nova star is a dense neutron star with the mass of the sun but only 17-miles wide; tough to lose weight on that orb. The radiation it emits, mainly gamma rays, sweeps across the cosmos toward earth at the rate of 30.2 times a second. That’s how fast it spins, or pulses. It’s a Pulsar. Seen from 4,500 light years away, I’m happy with this image, which contains 114, 10-second images stacked on top of each other and buffed with PixInsight software.

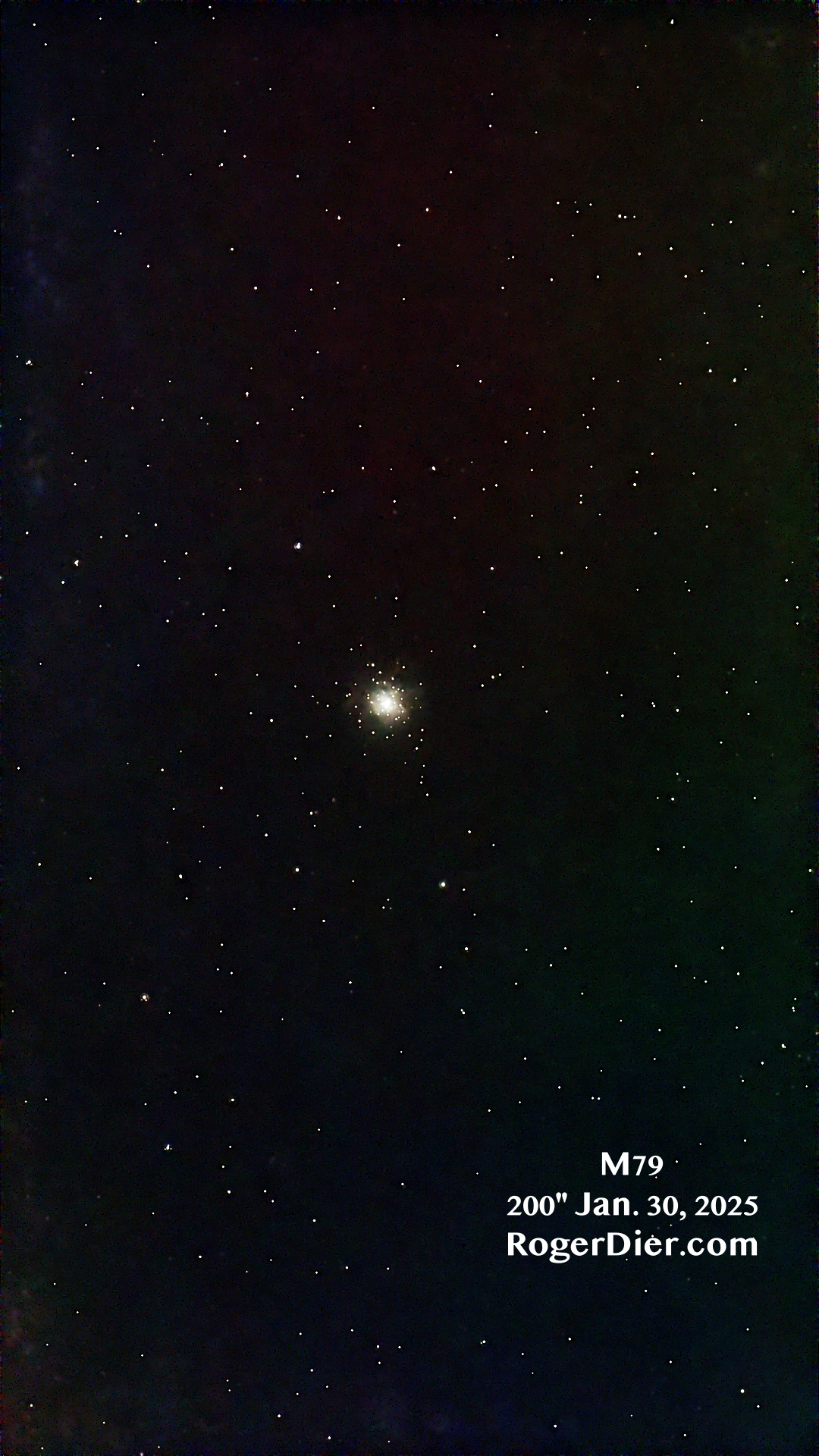

M79

Late in January I photographed M79, an object I had never viewed before. It’s 40,000 light years from Earth and 18 light years wide. M79 resides in the constellation Lepus the Rabbit. Lepus is south of Orion and even south of Canis Major. When I photographed it, it was barely 10-degrees over the southern horizon from 44-degrees north latitude. A pretty globular cluster in an odd place in the exurbs of our galaxy. Most globulars settled around the center hub of the Milky Way, but not snooty M79.

NGC 1788

Had I not had the SeeStar, I never would have seen NGC 1788, a lightly discussed blue-light reflection nebula on the boundary of Orion. The star powering the enterprise is a dim 10th magnitude star in the northwest sector of the cloud.

M42

We have all seen images of Messier 42, also known as the Great Orion Nebula. It’s the favorite winter song of northern hemisphere astronomers. M42 always invokes a peculiar feeling when one realizes what is happening before our eyes: A nursery for four new stars, with more on the way. I’ve always thought it looked like a celestial lagoon, with colorful filaments and waves of star-making ingredients spread out for light years before our eyes.

The location of the Crab Nebula is shown on TheSkyLive.com link below.

Thank you for reading Rogerdier.com.

If you are reading on a desktop, laptop or pad, subscribe for free at the bottom of this page.

https://theskylive.com/sky/deepsky/messier-1-the-crab-nebula-object